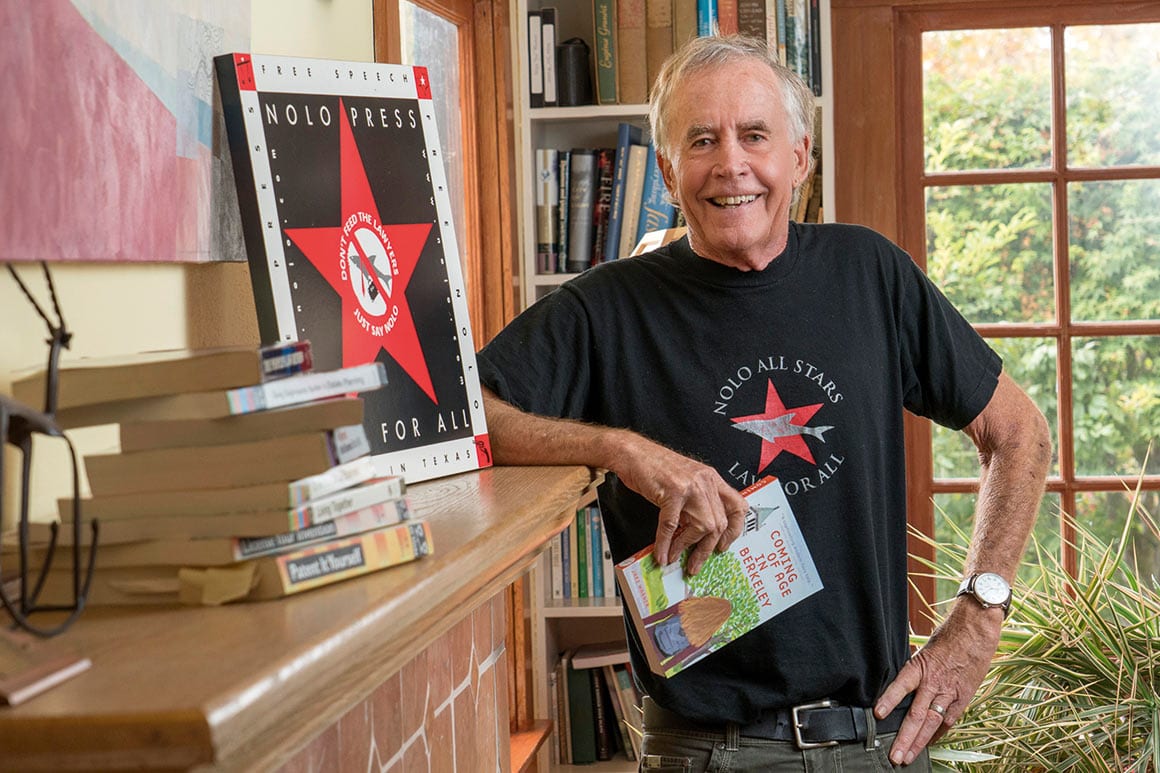

Nolo founder Ralph “Jake” Warner ’66 helped clear the path for four 2013 graduates who are rethinking legal services.

Interviewed by Andrew Cohen

The law movement’s do-it-yourself pioneer, Ralph “Jake” Warner ’66 always marched to an unconventional beat.

He shunned the security and serenity of an Ivy League Ph.D. program for chaotic, unfamiliar terrain 3,000 miles away. As Berkeley Law’s student association president, he led efforts that eliminated class rankings and redirected vending machine profits to minority student outreach. And while most classmates flocked to big law and DA offices after graduating, Warner joined Legal Aid in Richmond.

His legacy, of course, is Nolo—a four-letter word to the legal establishment soon after it launched in 1971. When publishers rejected their pitches for self-help legal books, Warner and Ed Sherman started their own shop. Nolo grew beyond their wildest expectations, churning out instructive guides that have helped millions of people save money by handling basic legal matters themselves.

The iconic books, software, and forms cover topics from divorce and immigration to wills and small-business formation. Warner ran Nolo for most of its first 40 years and wrote some of its best-selling books. The software came when personal computers gained popularity. Then Warner pounced on the internet boom, making Nolo the go-to site for free legal information.

Now retired, Warner has also advocated for reforms designed to make legal services and the justice system more accessible, written children’s stories, and just published his second novel.

Recently, he talked with Transcript Managing Editor Andrew Cohen about his colorful career.

Andrew Cohen: What sparked your interest in law school?

Ralph “Jake” Warner: I was going to get my Ph.D. in history and teach. Senior year at Princeton, sequestered in the library writing this intensive senior thesis, it hit me: I’ll spend the rest of my life in a carrel with the faint hope of carving out some niche of expertise on a 10-year period. I freaked out. My father and grandfather were lawyers, I didn’t want to go to Vietnam, and I wanted to get away from the East Coast. Law school seemed like a logical path.

Why Berkeley?

My advisor said UC had the best affordable law school west of the Mississippi, but I inadvertently applied to UCLA instead. I thought that was the “UC” he recommended. This was the early ’60s, long before the internet. I just didn’t know better.

So how did you end up here?

I’d read in the UCLA Law catalog that the school was founded in 1947. One night some friends come over for dinner and I say, “I’m going to this law school that was founded less than 20 years ago, but apparently it’s the best one west of the Mississippi.” Everyone starts laughing and I learn that Berkeley is the UC school my advisor recommended, not UCLA. Luckily, I still had two days before Berkeley’s application deadline.

What was law school like for you?

Boalt is so different now than it was when I was a student. I felt out of place. I thought the strict casebook method was a silly way to learn small points of law. I think there were eight women in my class, and hardly any minorities. That’s why I ran for student association president.

How did ‘Berkeley in the ’60s’ impact your experience?

There were a million things going on around us: the antiwar movement, the war on poverty, growing sensibilities about class and race, the free-speech movement. You’d think law students would be out front on that, but they weren’t at all. When I ran for student association president, I won by seven votes. I got very few votes from the 3Ls, probably split the 2Ls, and got nearly every vote from the 1Ls. That reflected an ongoing shift in ideas and ideals that happened at light speed in the mid-’60s.

What motivated your push to vastly curtail the use of letter grades?

Before that, the students were all ranked and obsessed with where they stood. It made for a tense environment. Professors were starting to get a little scared of students all over America, and I was pleasantly stunned that the faculty-student committee accepted our idea of abolishing grades. The culture was starting to change.

“We said, hey, we could make books like this accessible … in all kinds of legal subjects. It was a vast market no one was filling.”

How did your time at Legal Aid shape your perspective?

I’d planned to do environmental work in Washington, but I got divorced and didn’t want to be separated from my kids. Legal Aid in Richmond drew all sorts of interesting people from different backgrounds committed to making an impact. I grew up upper-middle class in Brooklyn and Westchester County. Suddenly, working in a low-income community with people who had never interacted with a lawyer before was really empowering.

Is that where the idea for Nolo was born?

Absolutely. The eligibility criteria for Legal Aid was so rigid. If you were just above the poverty line—say a market clerk or gas station attendant—you weren’t eligible. If you got a divorce, lawyers would set a high fee and people didn’t realize that half the country was in a way legally disenfranchised by silly rules and regulations that made no sense. I started to wonder why we couldn’t turn divorce into filling out forms and checking boxes. Why did every divorce need lawyers who held you over a barrel?

That first booklet, How to Do Your Own Divorce—was it the start of your broader publishing plan?

Not at all. Our third year at Legal Aid, the state did publish its first forms for divorce, and Ed Sherman wrote this booklet, which I edited. Soon after we’d left Legal Aid, we took it to a few other places around town, taught some classes in how to fill out the forms, small-scale stuff. It didn’t get any real traction until the head of the Sacramento County Bar Association stumbled onto it.

What happened?

He thought it was potentially dangerous to the public and that he needed to warn Californians about it. The day after the state legislature had de-convened, he issued a press release decrying our booklet. It was a slow news day, so every news channel and paper in the state carried it. That media attention essentially launched Nolo.

How quickly did things change?

Sales of How to Do Your Own Divorce went from around 300 copies over a six-month period to 3,000 a month. Now it has sold more than a million copies. We said, hey, we could make books like this accessible to the public in all kinds of legal subjects. It was a vast market no one was filling; the bigger publishers were afraid of getting sued by bar associations. By the time I retired in 2011, Nolo had sold more than 20 million books and software packages in dozens of legal areas.

How did Nolo capitalize on the internet explosion?

Our books and software had a strong track record with lawyers, most of whom grudgingly agreed that Nolo produced quality work. We knew the right online approach could help millions of people receive sound information about basic legal tasks and make the legal system more accessible. The California Judicial Council and others started putting forms and instructions online, which also helped. Still a long way to go, but we’ve moved past a lot of legal lingo and bureaucratic layers. Many more people now realize that lawyers are a valuable resource, but not essential for routine legal tasks.

What’s the most gratifying aspect of Nolo’s growth?

Advancing the belief that our legal system could be made more democratic, accessible, and affordable to the general public. It’s one of the ideas America was formed on, that the legal system is a huge part of our civil, civic, democratic process.

Looking back, is there a certain publication you appreciate most?

I’m proud of Will Maker, which we wrote in 1983. We’ve modified it over time, and it’s still useful because wills and trusts are largely the same as they’ve been for decades. Millions of wills have been accomplished through that product, which you can get at Costco for $40. More broadly, it’s great that more than a million people a month get free legal information online from Nolo.

You retired and sold your share of the business in 2011. What are you up to these days?

I’m taking courses at Cal through the Osher Lifelong Learning Institute, which is great fun, and I’m on the committee that helps pick its professors. I’ve taken an astronomy course, a film course on Bergman, and I’m about to take a course on Checkov. Also, my new novel (Coming of Age in Berkeley) just came out. I always liked to write, and after doing so much instructional writing for Nolo, fiction was a blast. I wrote a mystery novel with my wife in the ’80s, and this one is largely set on the Cal campus. It’s part love story, part thriller, and all Berkeley.