By Andrew Cohen

When public interest-minded law students assess a loan repayment assistance program, they naturally crunch the numbers and assess the data. But with new improvements to Berkeley Law’s already strong LRAP, Atteeyah Hollie ’10 urges a less micro and more aspirational approach.

“Berkeley not only talks the talk of wanting students to be social transformers, but it walks the walk by ensuring these students can dedicate their lives to it,” she says. “Fulfilling the audacious goal of creating social changers demands a full-on commitment to addressing the hurdles created by law school debt, and Berkeley Law’s LRAP does just that. I’m a walking, breathing example of what it can do for anyone wanting to commit their lives to social change.”

Now deputy director of the Southern Center for Human Rights in Atlanta, Hollie is thrilled to learn that the program just got even better.

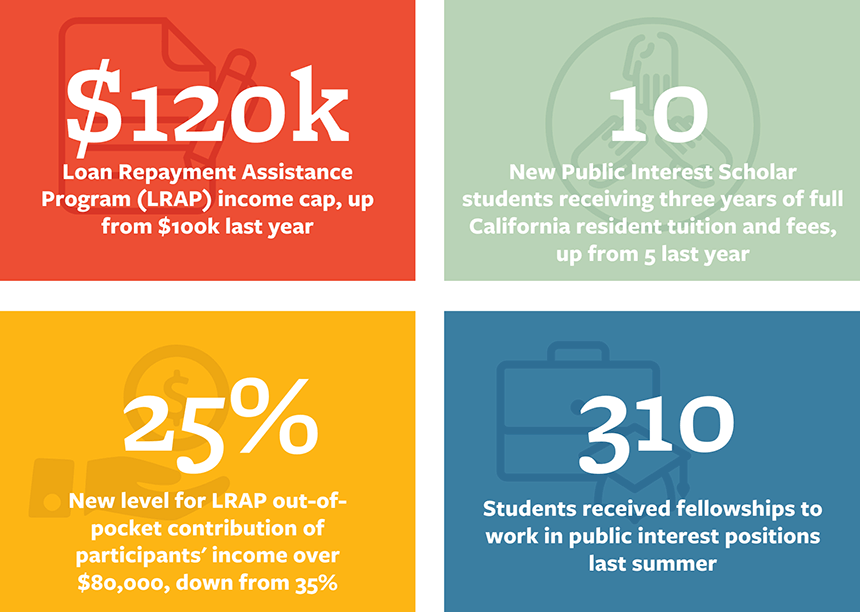

Berkeley Law has raised its LRAP income cap from $100,000 to $120,000, enabling more graduates to take advantage of this support. Meanwhile, the out-of-pocket contribution is now 25% of a participant’s income over $80,000, down from 35%, which means public interest graduates will receive more funding and spend less of their own money on student loan expenses.

“One of the defining characteristics of Berkeley Law is its public mission. Integral to this goal is supporting our graduates working in public interest after law school,” says Dean Erwin Chemerinsky. “Over the past few years, we’ve made a number of programmatic improvements to our Loan Repayment Assistance Program, in addition to increased outreach and communications. This is our most impactful policy change yet.”

Chemerinsky notes that Berkeley Law’s LRAP also has broad eligibility requirements that allow anyone in law-related, public interest employment to qualify for funding, including those working as judicial clerks and at private public interest firms.

“Participants have the flexibility to enter and exit the program at will, allowing graduates to follow their ideal career paths,” he says. “And Berkeley Law maximizes LRAP support by not considering assets, allowing for dependent deductions, and protecting a limited amount of side job income.”

Amanda Prasuhn, the school’s director of public interest financial support, calls Berkeley Law’s LRAP “now assuredly the best of any public law school.” She says it has one of the lowest out-of-pocket contribution formulas of any law school LRAP, even among private institutions, and that “compared with most other schools, we serve more graduates and graduates spend less of their own money on their student loans.”

Turning dreams into reality

Hollie works to decriminalize race and poverty within the criminal legal systems of the Deep South. Those efforts have included representing people facing execution, challenging human rights abuses in prisons and jails, demanding meaningful representation for those who cannot afford lawyers, and pushing for an end to wealth-based detention and extreme sentencing.

None of it would have been feasible without Berkeley Law’s LRAP, explains Hollie, who also credits her student time in the school’s Death Penalty Clinic and the East Bay Community Law Center’s Clean Slate Clinic as pivotal to cementing her career path.

“LRAP has made my time as a public interest lawyer possible, as it literally paid for my law school and undergraduate loans for 10-plus years,” she explains. “And now that my loans have been completely forgiven, I have many more years fighting for transformations in our criminal legal system to look forward to. Without LRAP, I’m not sure I could have lasted this long doing the work I love.”

Gregory Holtz ’13 taught at an Oakland public middle school before enrolling at Berkeley Law to learn how to address the barriers his students and families faced. As a staff attorney at Legal Services of Northern California, he represented tenants, benefits recipients, and students as they challenged practices and applications that kept them in poverty.

“Berkeley’s LRAP allowed me to pursue a career that directly impacted racialized and excluded communities and clients without needing to sacrifice to feed the debt monster,” he says.

Holtz thinks high-quality instruction and strong theory alone cannot produce the advocates that communities need to challenge the status quo. He says Berkeley Law’s program “addresses the financial realities that prevent graduates from pursuing public interest careers,” and that the school “continuing to expand and improve its program demonstrates its ongoing commitment to supply top-quality lawyers to clients and causes that need them.”

One piece of a powerful puzzle

The LRAP improvements are part of a far-reaching commitment to enable students to serve low-income and marginalized communities. Berkeley Law’s Public Interest Scholars program provides three years of full California resident tuition and fees for incoming students dedicated to public interest work. The school welcomed five incoming scholars when the program launched in 2021, and increased that support to fund 10 1L scholars this year.

The Career Development Office has broadened its advising services in this arena, and now has three dedicated public interest and public sector career counselors along with a full-time public interest program administrator.

Last summer, 310 students received fellowships that allowed them to work for nonprofit organizations, government agencies, and judges. More than half of students in the Class of 2024 (55%) received fellowships to support their 1L summer work, and 24% of students in the Class of 2023 received fellowships to support their 2L summer work.

“Everyone who qualified for a summer fellowship received one,” Prasuhn says. “Also, the Public Interest Career Support Committee launched a fundraising campaign to help provide some additional top-off funding to students who qualified for summer fellowships. Dean Chemerinsky matched the funds raised, and last summer’s fundraising effort was so successful that he agreed to match the amount raised again this year.”

Among public institutions in the top 20 ranked law schools, Prasuhn says Berkeley Law has the highest support threshold and income cap, and the most generous out-of-pocket contribution formula. And while some schools cut off participation for older graduates, or require alums to participate in LRAP for a set amount of time or lose benefits, she adds, “We’re flexible around when and how people can use our program. We also have no rules about the maximum or minimum amount of loan debt a participant can have to participate.”

Hollie says that although Berkeley Law prides itself on preparing social transformers of the future — people who will leave the world a better place than they found it — devoting one’s career to social justice work is simply not possible for people with crippling school debt.

“I arrived at Berkeley Law with unpaid college loans, and left with tens of thousands more in law school debt. I didn’t have any generational wealth to fall back on,” she says. “But the ambition to work towards a criminal legal system free from the taints of racism and classism, which Berkeley Law helped instill in me, never went away. LRAP allowed me to act on that ambition and to see it through.”