By Andrew Cohen

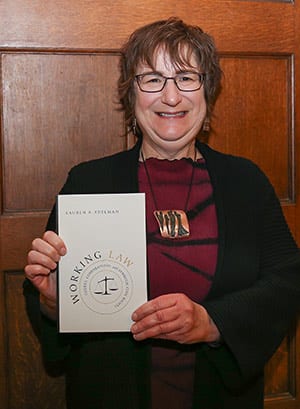

Professor Lauren Edelman ’86 received the first copy of her new book on November 7—election eve. “It’s not often the world changes the day after your book comes out,” she said with a sigh.

Edelman’s colleagues believe Working Law: Courts, Corporations and Symbolic Civil Rights could help change the world of workplace race and gender discrimination, which persists even though almost all companies have anti-discrimination policies in place. The former director of Berkeley Law’s renowned Center for the Study of Law & Society (CSLS), Edelman found that symbolic civil rights have replaced substantive civil rights.

“Our center has always been about changing the pace of social change and big ideas, and Lauren’s book reflects that,” said CSLS Director Jonathan Simon ’87, who moderated an event that celebrated the book on November 10 in Berkeley. “With this book, there’s an opportunity to do something far beyond the academic realm.”

The former associate dean of Berkeley Law’s Jurisprudence and Social Policy Program, Edelman won the 2000 Guggenheim Fellowship for her work on the formation of workplace civil rights laws. Working Law unearths a system of increasingly feckless policies and procedures that fail to dispel long-standing discrimination patterns.

“We’re seeing diversity equated with civil rights, and employers rewarding assimilation to white norms,” Edelman said. Her interviews with managers and analysis of hiring data showed that “law is now seen as a form of management—it’s equated with good personnel practices, while discrimination is reframed as bad management.”

Edelman noted that the law regulating companies is broad and ambiguous, allowing managers to shape what it means in daily practice. The book unpacks her theory of “legal endogeneity”—through which institutionalized organizational structures and practices influence judicial notions of legality and compliance.

Even though grievance, anti-harassment, evaluation and formal hiring procedures are often merely symbolic or ineffective, they are seen as proof of compliance with anti-discrimination laws “first within organizations, but eventually in the judicial realm as well,” Edelman said.

Her research showed that courts are increasingly relying on the mere presence of anti-harassment or anti-discrimination policies and personnel manuals to infer fair practices—without examining their effectiveness in combating discrimination.

“Even though anti-discrimination policies are in some cases doing little to advance the rights of women and people of color, judges increasingly see their presence as evidence of civil rights compliance and are too deferential to them,” Edelman said.

Judging the problem

At the event celebrating Working Law, commentator Nancy Gertner, a retired U.S. federal judge, called the book “an amazing translation from sociology of law to actual practice.” Now a senior lecturer at Harvard Law School, Gertner regularly sees judges using a “duck, avoid and evade” approach with discrimination cases. She explained how judges have “incentives to rifle through cases … every six months they have to report the number of cases they’ve closed.”

Gertner recalled her initial judicial training in 1992—when a session leader told a group of new judges, “Here’s how you get rid of these cases.” She cited a recent study of Northern District of Georgia judges who had dismissed 100 percent of civil rights claims, and “the development of devices to justify a defendant result. If there’s pressure to get rid of these cases, what better way than to classify a workplace act or remark as trivial or insubstantial.”

As a result, plaintiff lawyers further entrench this pattern. “They’re discouraging workers from filing because they know it’s an uphill battle in court,” Gertner said. “They don’t recognize that they can and should challenge the symbolism of these organizational structures.”

Commentator Catherine Albiston ’93, like Edelman, a Berkeley Professor of Law and Sociology, said Working Law will shine an important light on the problem. “What’s fascinating about this book, what sets it apart, is how (Edelman) shows that … organizations aren’t hostile to civil rights, they’re just steeped in institutional norms.”

Albiston said the book creates some cause for optimism, because it “shows that when judges defer to symbolic structures, they usually do so inadvertently.”

Further evidence of this lack of animus? “We found that liberal judges defer to symbolic structures more than conservative judges,” Edelman said. “They’re more impressed by the trappings of due process.”

Commentator Anna-Maria Marshall, a professor and head of the sociology department at the University of Illinois, said she was “very grateful for Lauren’s work, which is going to keep my grad students quite busy for the next couple decades.”