By Andrew Cohen

Interim Dean Melissa Murray apologized for breaking from tradition.

“Ordinarily, new faculty chair-holders give short remarks that focus on their research interests,” Murray said at a recent ceremony honoring her and four other Berkeley Law professors. Murray’s scholarship focuses largely on the legal parameters of intimate life—including marriage and its alternatives. “I must confess that over the last year, I’ve neglected my research a bit as I’ve focused on the work of the interim deanship. Besides, it would be entirely inappropriate for me to discuss my research on the problems with marriage, while my dear husband sits in the front row to support me,” she added with a smile.

In addition to Murray (Alexander F. and May T. Morrison Professor of Law), Christopher Tomlins (Elizabeth J. Boalt Professor of Law), Sonia Katyal (Chancellor’s Professor of Law) and Angela Onwuachi-Willig (Chancellor’s Professor of Law) discussed their career paths and recent scholarship.

Fellow honoree Kenneth Bamberger (Rosalinde and Arthur Gilbert Professor of Law), executive director of the school’s Berkeley Institute for Jewish Law and Israel Studies, could not attend. Murray relayed his appreciation and thoughts about his chair, funded through a foundation created by the Gilberts, who emigrated from England in 1949 and became real estate entrepreneurs.

“They were also incredibly philanthropic, with a special interest in causes involving Israel and the Jewish community,” Murray said. “It is entirely fitting that the Gilbert chair be given to Ken, whose research interests extend to both business law and Jewish law.”

Murray’s chair in public and municipal law was first bestowed by May Treat Morrison in honor of her husband, Alexander F. Morrison. Both graduated from UC Berkeley in 1878 and Alexander, who became a titan of the San Francisco legal community, regularly mentored junior colleagues.

“That has been a cornerstone of Berkeley Law for as long as I’ve been here, and a trait that has marked all prior occupants of the Morrison Chair,” said Murray, noting several predecessors—including the late Philip Frickey, who helped infuse the school with talented young faculty. “Phil exemplified the spirit of the Morrison chair because he recognized that for the law school to maintain its excellence, it had to double down on the future.”

Historical lessons for current conundrums

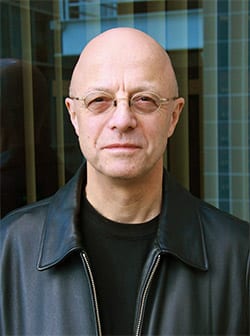

A renowned legal historian, Tomlins was recently elected an honorary fellow of the American Society for Legal History. While his scholarship delves into the past, he is clearly grateful for the present.

“This is good company to keep,” Tomlins said of his fellow honorees. “But so is the company of this faculty … amongst whom I’ve been lucky to find many new friends.”

Tomlins noted that the school’s Jurisprudence and Social Policy Program, where he now concentrates his efforts, has long been a beacon in his field. He teaches courses on the history and law of slavery, as well as legal history, and calls interdisciplinary socio-legal studies “the story of my career.”

An author of 11 books, Tomlins is currently researching the early 19th century Virginia slave Nat Turner and the violent events of August 1831 commonly labeled “the Turner Rebellion.” He said his efforts seek to “understand Turner himself and the ripples in antebellum American history that can be attributed to him.”

Technology through a civil rights lens

While a young lawyer, Katyal confronted myriad civil rights concerns within gender and sexuality—as well as technology and new media. She said her year and a half at Berkeley has enabled her to “conceptualize ways to bring these areas together. Much of this is due to my wonderful colleagues here who work in the fields of civil rights and social justice; and in intellectual property and technology.”

A co-director of the school’s Berkeley Center for Law & Technology, Katyal discussed her current paper, which focuses on the use of algorithms in legal matters and their intersection with civil rights concerns. She described how algorithms often discriminate against individuals based on protected characteristics, and their power to determine what “news” content appears online.

“On one level, we might think about algorithms in much the same way we think about law—as a set of abstract principles that are largely demonstrative of rational, objective manifestations,” she said. “Yet we now face the uncomfortable realization that the reality could not be further from the truth.”

While algorithms are widely hailed as reliable for being free from irrational biases of human judgment and prejudice, Katyal argued that they “are also the product of the design of their makers, who may miss evidence of systemic bias or structural discrimination.”

Cultural trauma past and present

Onwuachi-Willig, who joined the faculty last year, thanked fellow Berkeley Law Professors Herma Hill Kay, Kathy Abrams, Lauren Edelman, Angela Harris, Ian Haney López and john a. powell for “tearing down barriers that existed for women faculty and faculty of color prior to my arrival, and opened up pathways for scholars like me.”

Long interested in how the law is used to build and define communities, Onwuachi-Willig is assessing the impact of police killings of unarmed African Americans—and of the acquittals and non-indictments that often follow them—on the African-American population.

In a recent article, she described “cultural trauma” and the three elements that trigger it: A reoccurring routine harm that leads a subordinated group to expect it; widespread media attention that makes a large audience take notice of the harm; and public discourse about its meaning.

Onwuachi-Willig explained how such harms occur not only when a pattern is disrupted, but also when it is reinforced. “The continuation of what’s considered to be a given or expected subordination, usually through law or government sanction, creates the context in which a cultural trauma can be narrated,” she said.