By Andrew Cohen

Justice delayed isn’t ideal, but it’s better than justice denied — especially if the lessons gleaned help avert similar mistakes.

At its annual spring symposium on Jan. 28, the Asian American Law Journal at Berkeley Law commemorated the 40th anniversary of the coram nobis case overturning Korematsu v. United States. The event examined Korematsu’s importance, historical context, and ongoing pertinence in the face of global threats to civil rights.

In 1944, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the internment of nearly 120,000 Japanese Americans on the West Coast during World War II, ruling the detention a “military necessity” not based on race. At the symposium, attorneys who helped overturn Korematsu and others involved in two related cases described how the cases unfolded and what lessons they now offer.

Keynote speaker and Korematsu coram nobis legal team member Lorraine Bannai directs Seattle University School of Law’s Fred T. Korematsu Center for Law and Equality and Professor of Lawyering Skills. Outlining the history of exclusion and animosity against Asian Americans when they first arrived in the U.S., she said that in 1905 the Japanese and Korean Exclusion League declared, “We cannot compete with people who have such a low standard of civilization, living, and wages.”

Soon after Pearl Harbor was bombed on Dec. 7, 1941, Japanese Americans were removed from their homes — first to temporary confinement centers, and later to more permanent camps in desolate areas of the U.S. Fred Korematsu, an Oakland native and civil rights activist, resisted the internment and went into hiding before being arrested.

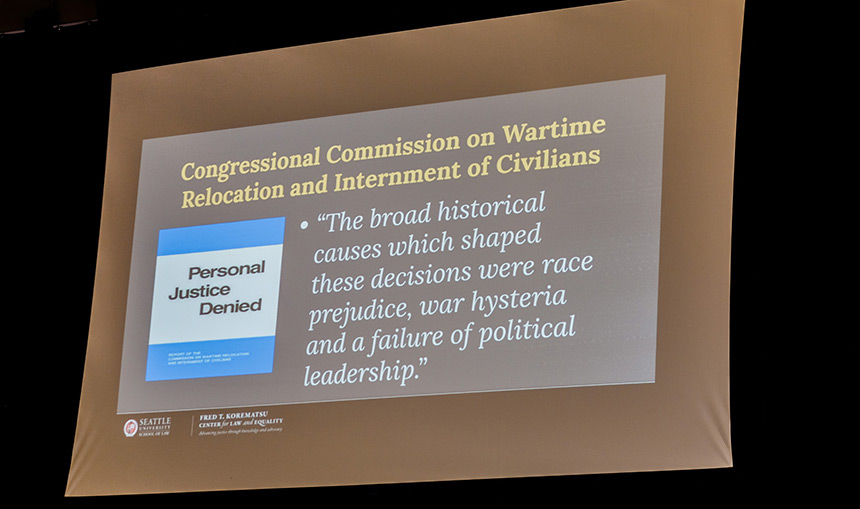

Stressing that there were no charges, trials, or evidence that anyone had engaged in espionage or sabotage, Bannai said: “The government argued that they had certain racial characteristics that made them prone to be allied to Japan, argued without proof that Japanese American children who attended Japanese language schools were subject to sources of propaganda, and that there was insufficient time to separate the loyal Japanese Americans from the disloyal.”

In Yasui v. United States, Minoru Yasui (the Oregon Bar’s first Japanese American member) challenged the constitutionality of the military curfew imposed on Japanese American citizens during the war, as did University of Washington student Gordon Hirabayashi in Hirabayashi v. United States.

In 1982, documents were discovered showing that while these cases were being argued before the Supreme Court, the government altered and destroyed evidence from intelligence agencies indicating that Japanese Americans posed no military threat to the U.S. The next year, a pro bono legal team including Bannai and fellow panelist Dale Minami ’71 filed identical petitions for each case in three federal district courts for a writ of error coram nobis, which asks the Court to rectify an error that led to a gross injustice.

A San Francisco federal district court judge granted the writ voiding Korematsu’s conviction, but explained that any legal precedent established by the case remained in force because it hinged on prosecutorial misconduct, not an error of law.

“The rights and human dignity of minorities have been compromised throughout history,” Bannai said. “The same stereotypes that led to wartime incarceration of Asians continue today are proven by recent anti-Asian hate crimes. The incarceration tells us that we all have to speak out. Very few stood up for the Japanese community and opposed the incarceration when it occurred.”

Dubious but determined

Minami recalled feeling skeptical when told about the effort to overturn Korematsu, but also eager to join it.

“This was going to be a massive undertaking,” he said. “We were going to retry history … to educate the public about the truth of these allegations.”

Co-founder of the Asian Law Caucus, the first nonprofit firm dedicated to Asian Pacific Islander legal advocacy, Minami also helped start the Asian American Bar Association of the Greater Bay Area, Asian Pacific Bar of California, and Coalition of Asian Pacific Americans. He described the strategy behind filing in three separate courts where each man originally brought his case instead of filing a consolidated case before the Supreme Court.

Assessing the Court’s conservative makeup at the time and seeing that separate cases provided multiple opportunities to make arguments, Minami said it offered “three bites at the apple to get a favorable ruling and a chance to appeal.”

Although the convictions were vacated in each case, the Yasui decision found no need to proceed with legal or factual findings. At the symposium, Yasui lawyer Peggy Nagae discussed that “bittersweet result,” and how things felt “unfinished and dissatisfied” when he died in 1986.

“There was no education for the public, and ultimately no healing,” said Nagae, who worked with Yasui’s daughter to form the Yasui Legacy Project. “He never got his day in court that he so wanted.”

Panelist Rodney Kawakami, an attorney for Hirabayashi, noted that Bannai’s sister Kathryn Bannai organized Hirabayashi’s legal team and that it was important for a Japanese American woman attorney to be its public face.

“At that time, there were very few,” he said. “The core team included a Latina, an African American, Chinese Americans, and Caucasians. They wanted the legal team to be diverse to reflect the principle that Gordon Hirabayashi stated: ‘This not just my case, or a Japanese American case. This is an American case.’”

In 1987, the U.S. Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals unanimously upheld a Seattle district court’s decision vacating both Hirabayashi’s forced removal conviction and his curfew conviction.

Historical boomerangs

During the second panel, Berkeley Law Dean Erwin Chemerinsky called Korematsu “a tragically flawed decision.” Discussing the 2018 Trump v. Hawaii case, in which the Supreme Court upheld then-President Trump’s executive order restricting travel to the U.S. by citizens from eight predominantly Muslim countries, Chemerinsky said, “Our country seems to be making the same mistake time and again.”

He added that the Court again assessed a group of people as dangerous on account of race, ethnicity, and national origin, with no evidence that they threatened national security.

“The Constitution exists to check the government’s power, especially in times of national crisis,” Chemerinsky said. “These cases saw a terrible abdication of the Supreme Court in its role.”

King & Spalding partner Quyen Ta ’03 was part of a group of lawyers with the Alliance for Asian American Justice that last year sued then-San Francisco District Attorney Chesa Boudin, after a violent attack on an Asian elder was pleaded down to misdemeanor assault instead of being charged as a hate crime.

Ta said the complaint was eventually withdrawn after it sparked productive discussions with Boudin and her office, and that a new initiative under current DA Brooke Jenkins focuses on issues the complaint raised regarding hostilities and access to justice.

“It’s really important to be a community lawyer no matter where you are,” said Ta, a Vietnamese refugee who worked at the Asian Law Caucus as a paralegal before law school and won Berkeley Law’s 2018 Young Alumna Award. “Cases aren’t files; these are people’s lives at stake. You can impact and effect social change in whatever environment you’re in.”

In 1988, the United States paid $20,000 each in reparations to over 82,000 surviving Japanese Americans who were interned. University of Hawaii Law Professor and Korematsu legal team member Eric Yamamoto noted that compensation alone isn’t sufficient: instead, the government apologizing for and acknowledging its wrongdoing “can lead to social healing of transgenerational injuries, and reduce the likelihood of repeating mistakes.”

He stressed the importance of teaching and learning about the cases — and to extend their international and human rights reach.

“The state secrets privilege encourages the government to exaggerate or lie about national security to justify civil liberties abuses,” Yamamoto said. “The coram nobis cases highlight what’s at stake when the government cannot hide: checks and balances to American democracy.”

Asian American Law Journal at Berkeley Law Editors-in-Chief Diana Lee ’23 and Kristen Smith ’23 contributed to this report.