By Andrew Cohen

Oscar Sarabia Roman ’21 grew up in a low-income, undocumented, immigrant household. Yet even with painstaking precautions—he did not get a driver’s license or leave California until high school for fear of getting caught—Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents still arrived at his family’s home in 2008, handcuffed Roman and his mother, and deported them to Mexico.

Because his father was a permanent U.S. resident, Roman applied to re-enter as his unmarried son. Four years, three rounds of interviews and medical testing, and more than 600 pages of application paperwork later, he was allowed to return.

In 2018, Roman won BARBRI’s One Lawyer Can Change the World Scholarship—chosen from more than 1,200 entries. In his essay, he vowed that receiving the scholarship would expand his ability to advocate powerfully for undocumented people across the country.

True to his word, Roman has been a fierce proponent of immigrant rights during law school. He is now one of three Berkeley Law students working as Thelton E. Henderson Center for Social Justice Racial Justice Summer Fellows, along with Emma Nicholls ’21 and Gaby Bermudez ’22.

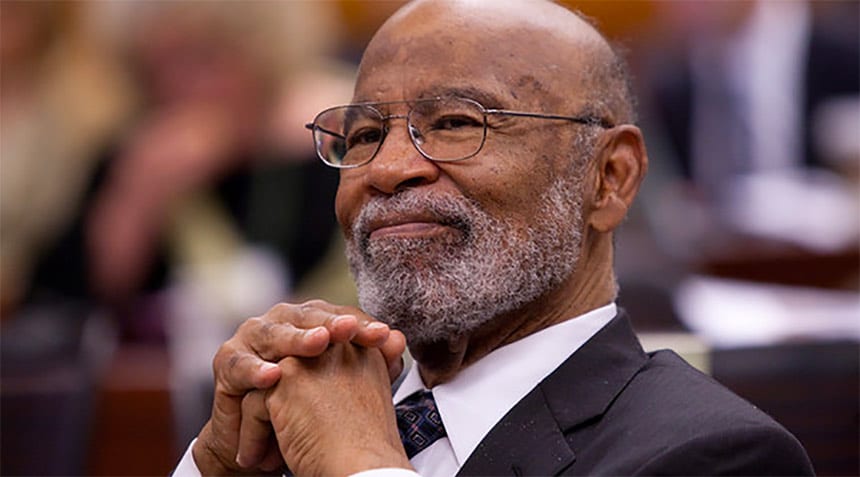

The fellowship, launched last year, honors Berkeley Law alumnus, iconic jurist, and revered civil rights advocate Thelton Henderson ’62. It is awarded annually to Berkeley Law students who have a demonstrated commitment to social justice and are engaged in racial justice work during law school.

Now interning with the American Civil Liberties Union Immigrants’ Rights Project, Roman assists attorneys by drafting memoranda, conducting legal research, and reviewing legal claims to help bring impact litigation cases aimed at changing draconian statutes and discriminatory rules.

“Immigration policy and laws in the United States have been mostly rooted in racism,” he says. “Although some progress has been made throughout the years, white supremacy still permeates our institutions and policies that thwart enduring progress for Black, Indigenous, and People of Color communities.”

With the ongoing pandemic, Roman works remotely in Berkeley rather than in a San Francisco office. His organization is paying close attention to coronavirus-related cases—and to change immigration laws that he describes as “racist, nativist, and xenophobic.”

“The fight for immigrant justice and racial justice entails combatting structural racism that prevents true justice and dignity for communities of color—both documented and undocumented,” Roman says.

Long-distance versatility

Nicholls spent last summer interning at East Bay Family Defenders, “where I saw firsthand how the child ‘protection’ system frequently targets, surveils, and punishes poor families and families of color.”

This summer, she is working with the Bronx Defenders’ Family Defense Practice and eagerly learning how its holistic defense model benefits New York families. She supports her supervising attorneys as they represent parents (mostly people of color, separated from their children at a far higher rate than white parents) who have been accused of child neglect or abuse.

COVID-19 has Nicholls working remotely from San Antonio (where her partner is in medical school) rather than the Bronx. While she meets with clients over the phone instead of in person, her workload remains high—and highly meaningful.

“I’m analyzing discovery, drafting motions, meeting with clients, and attending virtual court hearings,” Nicholls says. “I get the sense that my work is still largely the same as it would have been. Our interns participated in a robust orientation program, we’re completing a legal skills training program, and there’s plenty of work to do.”

COVID-19 has made it harder for parents to visit children who are out of their custody and to engage in certain programs that the New York Administration for Children’s Services requires them to complete before they can reunite with their children. Nicholls also notes that the agency has investigated families who had trouble adjusting to electronic learning during the crisis.

“The pandemic has had a dramatic impact on the lives of many of our clients, which shapes the way we advocate for them,” she says.

Nicholls calls racial justice a “central part” of the mission at Bronx Defenders, which recently launched a workshop series on anti-Blackness and a 24-hour hotline for race-oriented transgressions.

While recent public focus has highlighted how the police and criminal justice system impact ethnic minorities, Nicholls says the child welfare system is “also prejudicial and often causes lasting trauma to poor families and families of color.” She sees family defense work “as being essential to the racial justice and Black Lives Matter movements.”

Inspired by indigent defense

Leveling the legal playing field has long been a priority for Bermudez. As a UC Berkeley undergrad, she volunteered at Berkeley Law’s Death Penalty Clinic and East Bay Community Law Center, advocating for low-income, homeless, and incarcerated clients.

After graduating, she spent more than four years at the Eastern District of California’s Office of the Federal Public Defender. This summer, Bermudez’s fellowship brought her back to indigent defense at the Public Defender Service for the District of Columbia, where she works with the trial unit and supports an attorney who handles serious felony cases.

“One of the reasons I wanted to work at PDS this summer was because of its unique and nationally recognized approach to public defense,” she says. “The team prides itself on ensuring nobody is denied high-quality legal representation for simply lacking the means to pay.”

Bermudez works remotely out of San Diego, but feels a close connection to her cases despite living across the country. The pandemic has illuminated and exacerbated injustices that always needed attention, she says, and now are getting the focus they deserve.

Her organization is “fighting tooth and nail to get clients out of jails and prisons, where COVID-19 is running rampant, before it’s too late,” Bermudez says. As a result, much of her work includes compassionate release motions, letters urging transfers to home confinement, and motions requesting that pre-trial clients be released from custody.

Bermudez views racial justice as fundamental to public defense, and enjoys seeing co-workers fighting against race-driven inequities that are “deeply embedded in American institutions.” Attorneys in her unit recently joined a nationwide public defender protest and marched in support of justice for Black lives.

“I think it’s important to have an anti-racist framework in public defender offices,” Bermudez says. “Doing so helps call out the individual and systemic racism folks experience as they’re dragged through the criminal legal system.”

The three student fellows all strongly support the Black Lives Matter movement, and say that its success in dismantling structural racism is pivotal to effect substantial and enduring change.