By Andrew Cohen

Eager to tear down the machinery that drives capital punishment’s unequal application to people of color in California, Gov. Gavin Newsom and his legal office asked Berkeley Law Dean Erwin Chemerinsky if he would help write a brief focused on race and the death penalty.

Chemerinsky promptly joined forces with Professor Elisabeth Semel, director of the school’s Death Penalty Clinic, who summoned clinic students Catherine Harris ’21 and Marissa Lilly ’21 for assistance — and urgency.

“Lis’s first email to us described the project as a ‘fasten your seat belts’ situation, which was definitely accurate,” Harris says.

Two months and 75 pages later, Newsom’s amicus brief to the California Supreme Court was filed in People v. McDaniel, a capital case involving issues of racial bias in jury deliberation and sentencing decisions. The brief has sparked widespread media attention, marking the first time a California sitting governor filed an amicus brief about the death penalty’s uneven application.

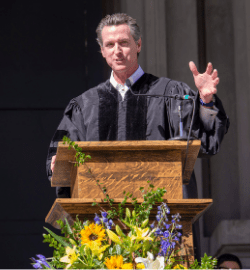

“Amid our nationwide reckoning on racism and historical injustice, the State of California is continuing to address the failings in our criminal justice system,” Newsom said in a statement. “California’s capital punishment scheme is now, and always has been, infected by racism … With this filing, we make clear that all Californians deserve the same right to a jury trial that is fair, and that it is a matter of life and death.”

Chemerinsky, Semel, and the students worked with Newsom’s legal affairs staff on the brief. It highlights the disproportionate impact of capital punishment on Black and Latinx Californians. The brief supports McDaniel’s position that, under California law, the jury must unanimously decide beyond a reasonable doubt the disputed aggravating circumstances and the life-or-death verdict.

“It is unprecedented for the governor of California to file a brief in the California Supreme Court against the death penalty,” Chemerinsky says. “The brief puts two main issues before the court — whether there should be a requirement of jury unanimity and proof beyond a reasonable doubt — in the context of the historic and current racism in the imposition of capital punishment. Professor Semel and Catherine Harris and Marissa Lilly did a superb job.”

The brief documents abundant evidence of such racial discrimination in capital cases from charging and how juries are selected to conviction and sentencing. It also demonstrates how social science research shows that the standards of unanimity and beyond a reasonable doubt reduce the influence of bias in jury decision-making.

Surprised and dismayed

Having worked on death penalty appeals in Texas after her first summer at Berkeley Law, Harris was stunned to see how much her research there mirrored what she found in California.

“California likes to think of itself as leading the way on progressive policies,” she says. “Naively, when I started my research, I expected that the state’s values would have translated to greater transparency and better guard rails on how the death penalty is administered here. I learned instead that California has been quite literally a national outlier in the number of death sentences it imposes, rivaling some of the numbers from Texas.”

Harris was also floored by the difficulty of finding information about known sources of racial bias, in particular data regarding the race of victims and defendants. With the help of the Habeas Corpus Resource Center, Berkeley Law’s team was able to help document the current extent of race’s role in the California death penalty, especially in Los Angeles County where McDaniel was prosecuted.

Harris’s research also amplified the relationship between Ramos v. Louisiana — where a jury convicted the defendant of murder by a 10-2 vote (before the U.S. Supreme Court reversed in April, deciding that the Sixth Amendment requires unanimous jury verdicts in trials for serious crimes) — and the 1990s push to end unanimous juries in California. Both undermined the credibility of Black jurors, Harris contends, conflating skepticism of law enforcement born from generations of lived experiences with “irrationality” and “bias.”

“Both saw racially diverse juries as a barrier to convictions and were really about making sure white people could maintain control of the criminal justice system,” she says. “Essentially, the only difference between the kinds of things people printed in Louisiana newspapers in 1890 and the L.A. Times coverage of ‘jury reform’ was that in 1995 the racism was slightly less overt.”

Lilly delved into the social science research that speaks to the effect of a unanimity requirement and a reasonable doubt standard on jury deliberations. Her research demonstrated how both radically alter how juries tend to deliberate, and can be effective safeguards against racial bias.

“The most rewarding aspect of working on the brief was being part of a team that directs the court’s attention to racism’s pervasiveness within the capital system,” Lilly says. “You can’t really have an honest discussion about the death penalty in America without discussing the racism that infects it at every stage.”

Pivoting toward California

The Death Penalty Clinic, led by Semel since it launched in 2001, has largely focused on litigation support for capital cases in the South. Over the last few years, however, Semel shifted some attention to California “because I thought there were new opportunities, especially to address issues of systemic racial discrimination.”

The clinic released a major report in June documenting how such discrimination is a consistent aspect of California jury selection. The exhaustive study investigates the history, legacy, and ongoing practice of excluding people of color — especially African Americans — from state juries through prosecutors’ peremptory challenges.

Semel and clinic students were instrumental in drafting Assembly Bill 3070, which Newsom signed into law on September 30. Among its provisions, the bill eliminates the requirement that the objecting party prove intentional discrimination, includes a list of presumptively invalid reasons for peremptory challenges, and requires courts to consider implicit and institutional bias.

In March 2019, Newsom issued a moratorium on executions and closed the execution chamber at San Quentin State Prison. In addition to AB 3070, he also signed AB 2542 to bar the use of race, ethnicity, or national origin to seek or obtain convictions or impose sentences.

Similar to their process for drafting AB 3070, Semel gave the students major responsibility in constructing the brief.

“Working with Catherine and Marissa on this effort was the optimal experience for a clinical faculty member,” Semel says. “They both became deeply knowledgeable about the issues, and thus able to collaborate with me in making critical choices about how we presented the facts and arguments.”

In addition to describing how people of color are excluded from juries, the brief reveals how their voices are diluted or silenced when they do serve. In doing so, it notes how jurors of color frequently have different experiences and perceptions of the justice system than white jurors and often are less likely to support death verdicts than their white counterparts.

Despite the frantic pace, Lilly calls working on the brief a deeply gratifying experience. “I’m really happy to have been a part of a team that had the opportunity to ensure that racism doesn’t go ignored in these vital discussions,” she says.