By Gwyneth K. Shaw

In the summer of 2020, as protests erupted all over the country in response to the murder of George Floyd by police officer Derek Chauvin, Berkeley Law Dean Erwin Chemerinsky felt optimistic that Congress and state legislatures would take steps to increase police accountability.

One way to do that is recasting the judicially-created doctrine of qualified immunity, which often in practice makes it all but impossible to successfully sue police officers over excessive force and other civil rights violations. But so far, that hasn’t happened.

“Even in California, a progressive state, none of the legislation to reform the police got through the legislature last year,” Chemerinsky said at a recent webinar on qualified immunity presented by Berkeley Law’s Civil Justice Research Initiative as part of the Berkeley Boosts executive education series. “Police unions are very powerful and they are very strongly opposed to any of these reforms, and given their political influence, we haven’t been able to overcome it yet.”

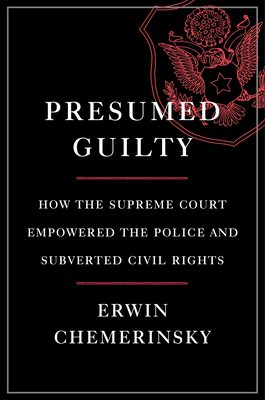

Chemerinsky, whose new book Presumed Guilty: How the Supreme Court Empowered the Police and Subverted Civil Rights argues that the high court has effectively enabled racist and excessively forceful behavior by police for decades, began with a history of qualified immunity and how the courts have handled it. The Supreme Court in particular has offered conflicting rulings about whether a two-pronged test is needed: first, whether the behavior violated a constitutional right, and second, whether the officer or government official is entitled to immunity.

Chemerinsky, whose new book Presumed Guilty: How the Supreme Court Empowered the Police and Subverted Civil Rights argues that the high court has effectively enabled racist and excessively forceful behavior by police for decades, began with a history of qualified immunity and how the courts have handled it. The Supreme Court in particular has offered conflicting rulings about whether a two-pronged test is needed: first, whether the behavior violated a constitutional right, and second, whether the officer or government official is entitled to immunity.

The first prong is bypassed altogether in many cases, Chemerinsky said, and judges often rule that officers are entitled to immunity. If rights are meaningless without remedies — the crux of the foundational 1803 Marbury v. Madison case — then the Supreme Court has largely gutted the remedy in these situations, he said.

“If the courts continually don’t decide whether there’s a constitutional violation, if they’re always dismissing based on qualified immunity, there never will established law and a basis for liability,” Chemerinsky said. “So I think the question is, how can qualified immunity be changed to make it less like absolute immunity?”

Finding solutions

The event, made possible by a generous gift from the American Association for Justice’s Robert L. Habush Endowment, also featured Suffolk Law School Professor Karen Blum, U.S. District Judge Carlton Reeves of the Southern District of Mississippi, and ACLU of Illinois Legal Director Nusrat Jahan Choudhury discussing where and how reform might happen.

“The doctrine of qualified immunity has has gotten a sort of popular recognition that it simply didn’t have for more than 100 years,” Choudhury said. “And it is very much tied to what’s happening in the social and political context of our day. The popular consciousness about qualified immunity has certainly increased in the context of the discussion of police reform.”

She noted that while federal efforts have stalled so far, there is movement at the statehouse level, in states including Colorado, New Mexico, and Minnesota, where Floyd lived. And there is growing momentum from a broad spectrum of ideological advocates, including libertarian-leaning voices arguing that greater accountability would help make policing safer because it would increase trust between law enforcement and the communities they serve.

Reeves, whose career before being appointed to the bench in 2010 included representing people suing police, upheld a qualified immunity grant in the 2020 case Jamison v. McClendon. But he wrote in his opinion that the traffic stop at issue should have been a Fourth Amendment violation if his hands weren’t tied by Supreme Court precedent, and his opinion argued that qualified immunity should be abandoned.

Juries, not judges, should be the ones deciding these questions, he said.

“The rules of civil procedure are designed to get to the truth, and if you can never invoke those rules, you can never get to the truth,” Reeves said.

Blum agreed.

“That is an underlying problem, because I can tell you, by looking to the judge’s name, frankly, whether they’re going to find the conduct objectively reasonable or not,” she said, invoking the standard judges are supposed to use. “And that’s not the way that your law should operate.”

Moving ahead

Chemerinsky argued that if local governments were held liable, then they would have much greater incentive to take the actions necessary to monitor and control police behavior, if only to save taxpayer dollars.

Choudhury wondered whether financial liability would really have that effect, pointing out that the city of Chicago has been paying out big settlements and awards for years while police misconduct continues.

Asked what lawyers, professors, and law students can do, the panelists offered role-based ideas but were unanimous on one thing: The time for advocacy and action is now.

“Some of what needs to be done is pushing for legislative reform,” Chemerinsky said. “A second thing that needs to be done by law professors, by law students, is to study and understand how qualified immunity actually operates in practice. We need to report this and we need to be advocates for change.”

Choudhury encouraged practitioners to understand how the entire puzzle fits together in these cases, which goes well beyond qualified immunity, to make the best case for clients. And Reeves urged lawyers to persist in pushing these suits forward, even when they’re hard.

“As practitioners out there, I would encourage you to bring these cases and represent these people who typically remain unrepresented,” Reeves said. “Do not discount these cases when they come to your door, because these people need your help.

“You are the ones who have the key to the courthouse and only you have that key. You have to open that door to the courthouse for these victims.”