By Gwyneth K. Shaw

Since fall 2016, Berkeley Law’s Human Rights Center Investigations Lab has blazed a trail for finding and presenting publicly-available evidence of international atrocities to inform and bolster cases in court.

With a new book co-edited by HRC Executive Director Alexa Koenig ‘13, those tactics are going global.

Digital Witness: Using Open Source Information for Human Rights Investigation, Documentation, and Accountability has just been published, and its first print run sold out almost instantly and hit the top spot in Amazon’s criminal evidence category.

Koenig worked with Daragh Murray, a professor of humanitarian law at the University of Essex’s Human Rights Center, and Sam Dubberley, head of the Crisis Evidence Lab at Amnesty International and a research fellow at the Essex Human Rights, Big Data, and Technology Project, to co-edit the book. As part of its launch in the United Kingdom last month, the trio spoke to Parliament and made a number of public appearances, including this podcast.

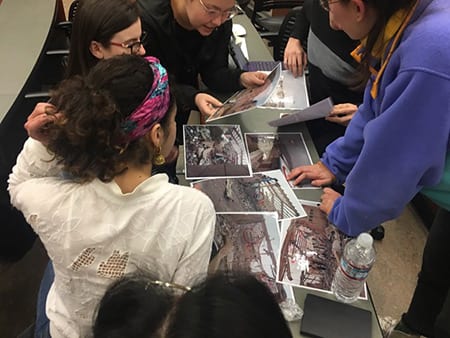

The three began working together in 2016 to establish the Digital Verification Corps, a group of university students from around the world trained to use digital methods to investigate alleged human rights abuses. The HRC’s lab was the first member of the corps, which now has six chapters on four continents and won a Times Higher Education Award for international collaboration last fall.

Rebuilding faith in facts

Digital Witness is a handbook for anyone using open-source material for investigations, and an effort to establish standards for dealing with the ethical, psychosocial, and cybersecurity challenges they can present. It’s also an attempt to rebuild faith in facts.

“Facts are the currency of human rights researchers, no matter their discipline; undermining a society’s trust in facts is a direct attack on the value of that currency. Perhaps even more importantly, access to accurate facts is critical to functioning democracies,” Koenig says. “Given the subject matter with which we work—human rights abuses and war crimes—the facts we unearth are often heavily and heatedly contested by those in positions of power, who may have abused their power in committing those atrocities in the first place, and may not want the truth to come to light.

“We hope that by helping to empower students, activists, researchers, and others to use these skills, we can help right that imbalance.”

Another objective is to bolster the evidentiary foundations of international criminal cases. Survivors’ testimony is critical, Koenig says, but corroborating materials are often needed to make a case airtight. Even if there are no survivors of an atrocity, online evidence can help, from social media posts to public databases.

One example is the case of Mahmoud Mustafa Busayf Al-Werfalli, a leader in al-Saiqa, an elite unit of the Libyan National Army. He was indicted by the International Criminal Court in 2017 on charges of murder and ordering the killing of non-combatants. The case marked the first time the court had issued a warrant based on videos found on Facebook.

Journalists are increasingly using this type of information, but the sheer volume of information can be overwhelming—like trying to find a particular needle in a haystack full of them. And it’s not just finding sources, it’s verifying them.

High stakes

“Lawyers, journalists and human rights organizations can’t afford to get facts wrong. The blowback, and the consequences for peoples’ lives, are too great,” Koenig says. “I truly believe it’s going to be increasingly important that law students and lawyers are trained in these methods. Digital Witness is meant to help with that.”

Beyond the book, HRC is leading an international effort, in partnership with the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, to create an international protocol for using open-source digital information to increase accountability for war crimes. That should be released this fall.

The center has also launched a professional training program at The Hague, working with the Institute for International Criminal Investigations and the Berkeley Advanced Media Institute at UC Berkeley’s Graduate School of Journalism to teach reporters, lawyers, and advocates how to conduct investigations according to the protocol.

Working with Murray and Dubberley on Digital Witness was inspiring, Koenig says, as was talking to so many people doing cutting edge investigations. Students, including those at Berkeley Law, were essential to the book and are making a growing impact, at organizations from The New York Times to Facebook to the International Criminal Court.

Koenig reports that this year’s cohort speaks 28 languages—so they can sift through digital information with ease.

“The students in our Investigations Lab, and throughout Amnesty’s Digital Verification Corps, are pioneers,” she says. “The thoughtfulness, creativity, and deep dedication they’ve brought to exploring how digital technologies can support justice, as well as how to do this work ethically and responsibly, is inspiring, as is the international network that has resulted in just three and a half years.”