By Andrew Cohen

Think you own all your ebooks, MP3 albums, and digital games? Think again. A new study by Berkeley Law alumnus Aaron Perzanowski ’06 and faculty member Chris Hoofnagle reveals consumers’ widespread misperceptions about ownership rights of their digital media.

As people continue to transition away from physical media—displaced by digital downloads and streaming services—conventional wisdom holds that owning an ebook is the same as owning a physical book. But while consumers have clear personal property rights in their tangible goods, their rights under digital media license terms are far more restrictive.

“Some in the tech industry suggest consumers don’t value those rights because buying digital content conveys an acceptance of more limited rights,” Perzanowski said. “We were skeptical of that explanation because it assumes that consumers have a nuanced understanding of licensing terms. Because those licenses are often thousands of words long, it should come as no surprise that consumers don’t read them. At the same time, marketing language like ‘buy now’ and ‘own’ sends the conflicting signal of familiar property rights.”

Eager to learn the scope of this misconception, Perzanowski enlisted Hoofnagle, a faculty director of the Berkeley Center for Law & Technology (BCLT). Together, they designed the first-ever empirical study of consumers’ perceptions of marketing language used by digital media retailers. A law professor at Case Western Reserve University, Perzanowski had worked with Hoofnagle as BCLT’s Microsoft Research Fellow from 2008 to 2009.

“We wanted to test how well people understand their rights when they click ‘buy now’ to acquire digital media,” Perzanowski said. “Sure enough, our study reveals that a significant number of consumers are being deceived by such transactions.”

Pushing for transparency

The researchers created a fictitious Internet retail site that simulated a popular commerce platform similar to online retail sites such as Amazon and Target. After the site surveyed a national sample of nearly 1,300 online consumers, Hoofnagle and Perzanowski analyzed their perceptions through the lens of false advertising and unfair and deceptive trade practices.

After choosing a particular item, each respondent was shown one of four product page variations. Three presented digital goods with different transaction labels: “Buy Now,” “License Now,” and a short notice listing acceptable and impermissible uses of the item. The fourth variation featured a physical good with the standard “Buy Now” button.

Respondents were then instructed to review that page as they normally would when acquiring media goods online. Of the 970 respondents who viewed digital product pages, only 14 clicked the “Terms of Use” link.

“Aaron came up with this innovative idea that I’ve never seen in advertising copy testing,” Hoofnagle said. “It was a great way to get survey respondents involved in the process.”

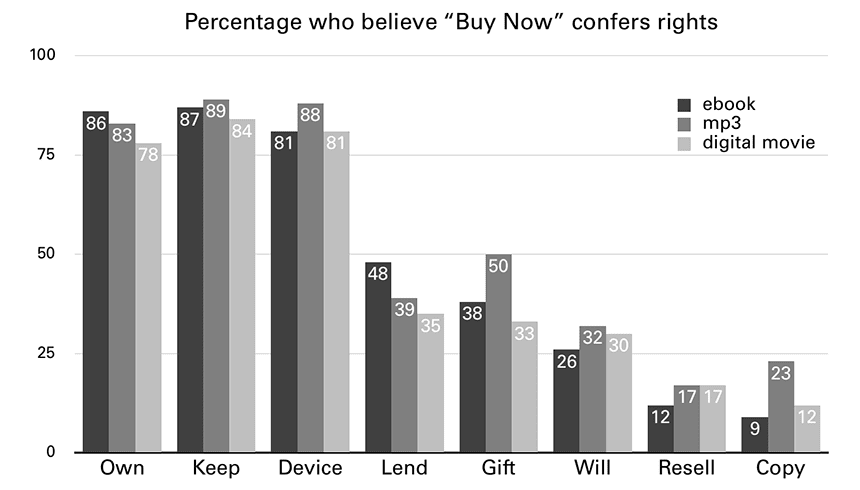

The results showed that a significant subset of consumers, in many cases a majority, believe they enjoy the same rights to use and transfer digital media goods as they do with physical goods. The survey also strongly indicates that these ownership rights matter to consumers. Responses demonstrated that people are willing to pay more for such rights and are more likely to obtain media elsewhere—both legally and illegally—in their absence.

Digital product sellers do note in consumer contracts that content rights may not be sold, rented, leased, distributed, modified, or otherwise assigned. Apple’s iTunes Store even explains that the company can “change, suspend, remove or disable access to any iTunes products … at any time without notice.” In 2009, a copyright dispute prompted Amazon to electronically erase two George Orwell books from purchasers’ Kindle e-readers, and then provide refunds.

Digital retailers’ continued ownership rights of the products they sell are plainly protected by law. But the study shows that those rights are buried in long contractual langue rather than communicated openly to consumers.

A proposed solution

In response to the study’s findings, Hoofnagle and Perzanowski propose a simple way for retailers to reduce these misconceptions: adding a short notice to a digital product page summarizing consumer rights in plain language.

“We expect that the evidence we present will create an incentive for retailers to respond, especially since we’ve outlined an effective and low-cost way to address this issue,” Perzanowski said. “That pressure is likely to grow as public awareness increases and the risk of litigation or public enforcement becomes apparent.”

If retailers fail to respond, Perzanowski and Hoofnagle will approach the Federal Trade Commission (FTC)—again. They recently met for about 90 minutes with several FTC lawyers in Washington, D.C., who are responsible for investigations concerning digital media sellers.

Sales of digital products generate hundreds of billions in revenue each year. The study notes that if consumers understood the limited rights obtained with these purchases, the market could shift through reduced prices or new business models that offered expanded rights.

“Given its limited resources and the wide swath of the economy it’s responsible for regulating, the FTC likely wants to focus on the biggest deceptions facing consumers,” said Hoofnagle, who authored a recent monograph on the agency. “We think our study goes a long way to establishing a collective multi-billion dollar injury to consumers.”