By Gwyneth K. Shaw

A California congressman’s proposal to make forensic algorithms more transparent to criminal defendants has strong ties to two Berkeley Law professors, Rebecca Wexler and Andrea Roth.

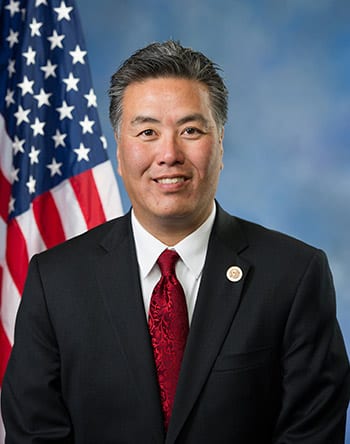

The newly introduced bill, sponsored by Rep. Mark Takano, would amend the Federal Rules of Evidence to ensure that owners of proprietary algorithms can’t use the trade secret privilege to avoid sharing information about the program with defendants. It also would guarantee defendants access to a working version of the software, with the data needed to reproduce the results presented in court, and create a standards and testing program for forensic algorithms through the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST).

Via @RepMarkTakano

To address this injustice, I introduced the Justice in Forensic Algorithms Act.

This bill ensures that defendants can access source code to challenge evidence used against them. It also sets standards and testing to assess whether forensic algorithms are fair enough to be used. pic.twitter.com/nkkDCi577Y

— Mark Takano (@RepMarkTakano) September 17, 2019

Shaping legislation

Emily Paul, a Berkeley School of Information graduate who works in Takano’s office as a TechCongress fellow, managed the development of the legislation.

“Our legislation looks to safeguard defendants by opening up the rules of evidence so that trade secrets aren’t privileged over the rights of defendants,” says Takano, a Riverside County Democrat. “It’s essential that defendants and their attorneys be able to examine how the algorithms work and the underlying data that powers them.”

The seed for the bill came from Wexler’s 2015 Slate op-ed, “Convicted by Code,” which outlined how some criminal defendants were being denied access to the guts of the programs used to make a DNA match or pinpoint their location.

The algorithms’ owners and developers, which in some cases are governmental entities, such as the New York City Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, have successfully argued that the details of the code are trade secrets that must be protected from the prying eyes of competitors—and defense attorneys.

“It just struck me as wrong,” Wexler says.

A level playing field

Errors in algorithms—or inadvertent coding that can amplify racial and gender bias—are well documented. What’s just as important from Wexler’s point of view is that civil trade secret cases typically include an opportunity for defendants accused of misappropriation to gain access, in a controlled, private way, to the trade secret in question in order to defend themselves.

“That’s something that the law is doing for businesses and for innovators,” she says. “Why can’t the law also do that for criminal defendants, when the stakes can be someone’s life or liberty?”

In criminal cases, courts are simply turning defendants down over the trade secret argument, she says, creating a “black box” problem where defendants can see only the data that goes in and comes out of the program—not what happens within it.

Increasingly common, these algorithms are being used at every stage of criminal proceedings, from gathering evidence to making sentencing and parole recommendations. Roth, whose work has long focused on the impact of science-based prosecutions on evidence law, says the science holds great promise in making proof more accurate. But, as a wave of exonerations based on DNA evidence has shown, forensic evidence isn’t foolproof.

“Using complex software to do forensic analysis also holds much promise in correcting some of the bias, inaccuracy, and imprecision in traditional forensic analysis,” she says. “But the level of sophistication of proprietary algorithms now used to generate proof of guilt is unprecedented, and something that existing rules of evidence are not fully equipped to deal with.”

A member of the Legal Resource Committee of NIST’s Organization of Scientific Area Committees for Forensic Science, Roth worked with Takano’s staff to incorporate the idea of standards into the bill.

“NIST is a well-respected agency with a culture of open inquiry and robust research, and is beholden neither to the defense, the prosecution (say, the Department of Justice) nor industry,” she says.

Berkeley Law’s imprint

Roth and Wexler are faculty co-directors of the Berkeley Center for Law & Technology. In their own work, each cited a student note in the California Law Review on computer code, intellectual property, and criminal prosecutions written by Christian Chessman ’18.

They also were influenced by the work of BCLT Co-director Jennifer Urban, who has advocated for open source software in public law realms. Urban is a clinical professor who directs Berkeley Law’s Samuelson Law, Technology & Public Policy Clinic.

Wexler’s Slate piece, she says, “joined a conversation where there were really powerful voices already contesting these denials.” One group leading the way was the Legal Aid Society in New York City, where Wexler spent a year as a public interest fellow.

Those lawyers, though, “weren’t challenging the idea that trade secrecy was even a legitimate shield in this context,” she says. “So I found that I could contribute by saying, ‘This is not why we have trade secret law.’”

In 2018, she published a paper in the Stanford Law Review that expanded her argument and asserted case that the trade secret privilege shouldn’t be allowed to stop disclosure in criminal cases. Takano’s bill adopts that idea through the amendment to the federal rules, something Wexler thinks will move states in the same direction.

“The Federal Rules of Evidence are a model for a lot of states, so making a change there should have a ripple effect,” Wexler says.

She adds that software developers are concerned about leaks, but courts are equipped to handle that problem now.

“Criminal defendants aren’t threatening to steal the company’s trade secrets. They’re subpoenaing evidence,” she says. “These aren’t the same thing. Defending your client from criminal charges isn’t the same thing as announcing yourself as a business competitor.”

Takano says Wexler’s initial Slate piece alerted him and his staff to the issue , and that the conversations continued over the years with help from Roth, Paul, and other staff members. Congress has fallen behind the curve, Takano says, when it comes to understanding and regulating the most modern technology.

To get there, lawmakers need the help of experts and scholars, he says.

“It’s incredibly important that people like Rebecca Wexler and Andrea Roth, who are scholars and thinkers and who are focused on identifying weaknesses in our criminal justice system, are able to find a listening ear on Capitol Hill,” Takano says. “It takes people like them, who are supported by institutions like Berkeley Law, but we’ve also got to have people who are receptive to what they’re doing.

“I’m very thankful that people like Rebecca and Andrea exist.”