This essay is drawn from both Herma Hill Kay, Breaking into the Legal Ivory Tower: The First American Women Law Professors (University of California Press, forthcoming 2020) and Sandra P. Epstein, Law at Berkeley (Institute of Governmental Studies Press, 1997).

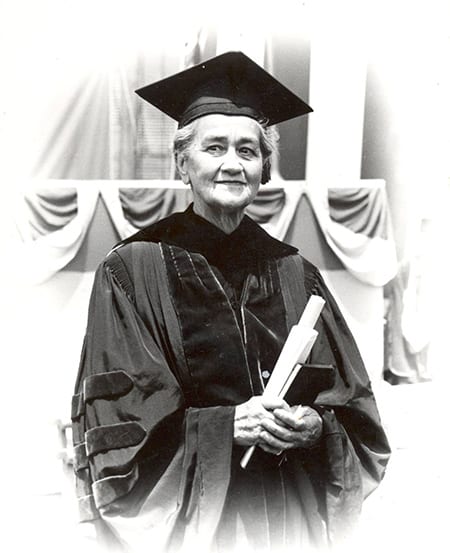

Barbara Nachtrieb Armstrong was Berkeley Law’s first, and until 1960, its only woman law professor. When she began teaching as a lecturer in the Department of Economics and the School of Law in 1919, she was the first and remained for several years the only woman to have such a position at an accredited American law school.

She was extremely influential in the adoption of the Social Security Act of 1935 and was a lifelong advocate of minimum wage legislation, universal and publicly funded health insurance, disability insurance, and old-age benefits. By the time she retired in 1957, only nine other women had been appointed to teach at ABA-approved law schools in the United States. She blazed the trail that all other women law professors have followed.

Barbara Nachtrieb entered Cal as an undergraduate in the Fall of 1909. She studied economics and gained her lifelong interest in social insurance while studying with Professor Jessica Blanche Peixotto in the Department of Social Economy. Peixotto, who herself was a legend, became Cal’s first woman full professor in 1918. Nachtrieb earned her A.B. degree with honors in Jurisprudence in 1912 and her J.D. in 1915 from what was then known as the School of Jurisprudence at Berkeley, but soon to become the School of Law.

In 1916, Gov. Hiram Johnson appointed Nachtrieb to be the executive secretary and director of surveys of the California Social Insurance Commission. She worked with the commission in Sacramento until 1919, developing a proposed universal health insurance system. The reform legislation failed to pass and failed again in the late 1940s, when Nachtrieb worked with Gov. Earl Warren to provide for universal health insurance in California.

Nachtrieb returned to Berkeley and earned a Ph.D. in economics. She officially joined the Berkeley law faculty as an instructor in Social Economics and Law in 1922, a year after the birth of her daughter. She became an assistant professor in 1925 and a tenured professor in 1929. Nachtrieb, with daughter and nanny in tow, traveled Europe in the 1920s studying social insurance systems. That research provided the foundation for her expertise in social insurance and also her work on the Social Security Act. While conducting this research and teaching, Nachtrieb divorced, married Ian Armstrong in 1926, and became known thereafter to students as Mrs. Armstrong.

Her work on health insurance reform in California in the teens and on European social insurance systems in the ’20s led her to develop what she considered a “well rounded” scheme of social insurance for the United States. In one form or another, many of her ideas were enacted, partly through her efforts, during the New Deal. Her book Insuring the Essentials: Minimum Wage Plus Social Insurance—A Living Wage Program (1932) established her as one of the country’s leading experts on social insurance. It laid out her vision of a minimum wage to ensure an adequate standard of living; a program of social insurance to keep this standard intact when no wage can be earned; Worker’s Compensation insurance to cover the risk of occupational injury or illness; “social health insurance” for other illness; pensions for older people and for those who become disabled from work (which became part of the Social Security Act); survivors’ insurance to support families in the event of the death of the breadwinner; and unemployment insurance. The economic devastation of the Great Depression provided an opening for Armstrong to put her ideas into legislation.

In June 1934, when unemployment reached levels not seen before, President Franklin Roosevelt created the Committee on Economic Security and named Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins as its chair. The charge to the committee was to study “problems relating to the economic security of individuals” and to make recommendations to ameliorate them. Tom Eliot, the Assistant Solicitor General, sent a telegram to Armstrong saying the president wanted her to come to Washington to work as a consultant to the committee. Armstrong signed a contract to serve as a consultant to the committee both on unemployment insurance and old-age insurance. She took a leave from the university for the fall semester of 1934 and left for Washington.

Many controversies arose in the planning for a social insurance system. One was whether it, and especially the unemployment compensation program, should be a federal system or a federal-state cooperative system modeled on one recently enacted in Wisconsin. Another was how unemployment insurance and old-age insurance should be funded. A third — a problem that Secretary Perkins deemed “almost insuperable” — was whether the Supreme Court would hold it unconstitutional. Armstrong had developed her own positions on all of these disputed points in her 1932 book, well before her arrival in Washington. She recommended that the committee propose compulsory old-age insurance on a national scale, supplemented with a federal subsidy for the assistance programs that already existed in many states. She also advocated a national system of unemployment insurance rather than the Wisconsin federal-state plan, which permitted voluntary employer contributions and which she deemed fiscally unsound.

Eliot objected to the plan on the ground that it was unconstitutional. Armstrong disputed his opinion, relying on a brief prepared for her by constitutional law professors at Berkeley and Duke. Eliot replied that Professor Thomas Reed Powell of Harvard said it was unconstitutional. Not to be outfoxed, in characteristic fashion Armstrong got on a train and went to Cambridge to meet with Powell, whom she had befriended when he visited at Berkeley. Powell said that national old-age insurance was not unconstitutional and wrote a note to Eliot saying that in his view a national compulsory old-age insurance system would be constitutional.

Armstrong’s position on national funding was vindicated, but only for old-age insurance. The Social Security Act of 1935 contained a compulsory national old-age retirement annuity plan financed by taxes on both employers and workers. In her 1936 article describing the law, Armstrong characterized the old-age security part of the statute as “directed at the prevention of destitution rather than its relief.” Unemployment insurance, however, emerged as a federal-state unemployment compensation plan, not the federal plan that Armstrong supported.

Having completed her work on the Social Security Act, Armstrong returned to California in 1935. She was promoted to full Professor of Law that year at a salary of $4,000, a sum that was $1,000 below what the law faculty had authorized as the lowest salary for a full professor in 1921. And it took the faculty longer to promote her to full professor than for men.

Armstrong was one of the law school’s most admired teachers. She taught courses in Law and Poverty Problems, Law of Persons, Industrial Law (later known as Labor Law), Social Insurance, and Community Property (a forerunner of Family Law). Her former student and colleague Professor Emerita Babette Barton reports that students took classes from Armstrong just because she was teaching them. She also regularly hosted lunches for the few women law students and regaled them with tales of her early days of teaching, including the story of the reporter who climbed up the side of the building to view the freak who was a woman law professor. She also described the humiliation of going to faculty meetings at the Men’s Faculty Club, where women were not allowed to tread on the floor of the Great Hall Dining Room. She had to be carried across to the meeting room by her male colleagues. Understandably, then, Armstrong became one of the founders of the Women’s Faculty Club on the Berkeley Campus.

She also wrote numerous law review articles and many books. Her two-volume study of California family law became the basic work in the field and led to important reforms. It was not until shortly before she retired that her salary was finally made in parity to that of her male colleagues. In 1954, she was named the A.F. and May T. Morrison Professor of Municipal Law. At the time, she was the only woman law professor in the country to hold a named chair.

For all these professional achievements and her innovation on public policy, it should be said that Armstrong was also equally committed to domestic life. Her story is not complete without noting her devotion to her family and the husband she so admired.

Catherine Fisk, Barbara Nachtrieb Armstrong Professor of Law