By Gwyneth K. Shaw

Like a slew of innovations that preceded it — from the telegraph to nanotechnology — artificial intelligence is both changing a wide swath of our landscape and raising an equally broad set of concerns.

At Berkeley Law, a Silicon Valley neighbor long renowned for its top technology law programs, the faculty, students, research centers, and executive and Continuing Legal Education platforms are meeting the challenges head on. From different corners of the legal and policy world, they’re in position to understand and explain the latest AI offerings and highlight places where guardrails are needed — and where a hands-off approach would be smarter.

This summer, the school will begin offering a Master of Laws (LL.M.) degree with an AI focus — the first of its kind at an American law school. The AI Law and Regulation certificate is open for application from students interested in the executive track program, which is completed over two summers or through remote study combined with one summer on campus.

“At Berkeley Law, we are committed to leading the way in legal education by anticipating the future needs of our profession. Our AI-focused degree program is a testament to our dedication to preparing our students for the challenges and opportunities presented by emerging technologies,” Dean Erwin Chemerinsky says. “This program underscores our commitment to innovation and excellence, ensuring our graduates are at the forefront of the legal landscape.”

The certificate is just one of several ways practitioners can add AI understanding to their professional toolkit. Berkeley Law’s Executive Education program offers an annual AI Institute that takes participants from the basics of the technology to the regulatory big picture as well as Generative AI for the Legal Profession, a self-paced course that will open registration for its second cohort in November.

At the Berkeley Center for Law & Technology (BCLT) — long the epicenter of the school’s tech program — the AI, Platforms, and Society Center aims to build community among practitioners while supporting research and training. A partnership with CITRIS Policy Lab at the Center for Information Technology Research in the Interest of Society and the Banatao Institute (CITRIS), which draws from expertise on the UC campuses at Berkeley, Davis, Merced, and Santa Cruz, the BCLT program also works with UC Berkeley’s Goldman School of Public Policy, School of Information, and College of Engineering.

The center also hosts AI-related events, which are available on its innovative B-CLE platform. So does the Berkeley Center for Law and Business, with webinars and in-person talks with expert corporate and startup leaders.

Drilling down

Many of BCLT’s 20 faculty co-directors have AI issues as part of their scholarship agenda, including Professors Kenneth A. Bamberger, Colleen V. Chien ’02, Sonia Katyal, Deirdre Mulligan, Tejas N. Narechania, Brandie Nonnecke, Andrea Roth, Pamela Samuelson, Jennifer M. Urban ’00, and Rebecca Wexler. Their expertise spans the full spectrum of AI-adjacent questions, including privacy concerns, intellectual property and competition questions, and the implications for the criminal justice system.

“The most important potential benefit of AI is harnessing the power of the vast amount of information we have about our world, in ways that we’ve been stymied from doing because of scale and complexity, to answer questions and generate ideas,” says Urban, who’s the director of policy initiatives at the school’s Samuelson Law, Technology & Public Policy Clinic.

“The potential drawbacks stem from the risk of that we fail to develop and deploy AI technology in service of those benefits, but instead to take shortcuts that destroy public trust and cause unnecessary damage. A big use of automation already, for example, is automated decision-making,” she says. “Unfortunately, some automated systems have been prone to bias and mistake—even when making critically important decisions, like benefits allocations, healthcare coverage, and employment decisions. Ultimately, any decision-making system requires trust. We risk creating—or not interrupting—incentives that nudge the development of the technology away from publicly beneficial uses and toward untrustworthy results.”

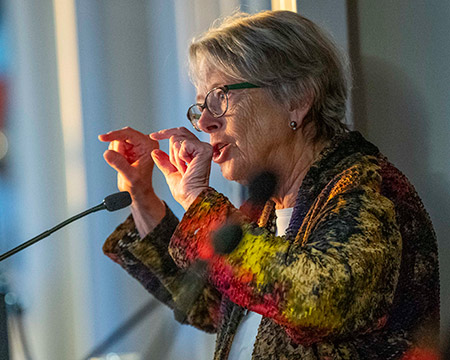

One of the more pressing issues at the moment, Samuelson says, is even agreeing precisely what constitutes AI. A pioneer in digital copyright law, intellectual property, cyberlaw and information policy, she recently spoke to the Europe’s Digital Agenda Conference at the University of Bergen about the United States’ perspective on the current landscape.

“If you have a technology that’s well-defined, and everybody knows what it is and what it isn’t, that’s one thing,” she says. “But nobody has a good definition for what artificial intelligence is, and today, the hype around that term means that people are calling pretty much every software system AI, and it’s just not.”

Some companies are genuinely building and refining large language models and other neural networks that could profoundly change the creative sector and reorient a host of business models. Others are just jumping on a next-new-thing bandwagon that just recently held out non-fungible tokens (NFTs) and cryptocurrency and blockchain as world-altering innovations, Samuelson says.

“Not so long ago, there was this sense that they were going to sweep away everything and we need a whole new body of regulations for them. But no, they turned out to be kind of marginal phenomena,” she adds. “I don’t think that AI systems are marginal phenomena, but I don’t think they’re one thing, either.”

In her European presentation, Samuelson said copyright law is the only U.S. law on the books that could “bring AI to its knees.” Multiple cases are pending in courts across the country from heavy hitters in the creative world, including The New York Times and Getty Images, alleging that scraping those companies’ original works to train generative models that then create new visual and text-based works violates copyright laws.

AI companies often argue that their tactics constitute a “fair use” under the current federal copyright laws — a question that’s been well-litigated in cases involving music and online books, to give just two examples. But Samuelson says a sweeping judgment about AI seems unlikely.

Narechania, whose work on AI and machine learning led to an invitation to the White House earlier this year to comment on President Joe Biden’s policies, says the competition angle raises other big questions.

“If you take a look at the companies playing in this space, there are fewer and fewer of them, they tend to be more concentrated, they tend to be overlapping. And that has implications for both competition and innovation,” he says. “AI appears to us as a magic technology. You go to ChatGPT in your browser, type something in, get a response, it’s fun. But once you peek under the hood and look at what the technology stack looks like underneath it, you see a funnel that narrows pretty quickly. There are lots and lots of applications, but a bunch of them are all sitting on top of GPT — that is, there is only one model of language.

“And that funnel, that lack of competition below the application layer, has problems. What is the quality going to be of these models, to the extent we’re worried about bias or discrimination or risk? What’s the data that are input into these models? Who’s getting it? Where is it coming from?”

Multiple providers could help improve these systems through market competition, Narechania adds. If that’s not possible, regulations might be necessary to ensure the public gets a real benefit out of the technology.

Eyes everywhere

Just 20 years ago, the notion of catching a criminal suspect using publicly-mounted cameras and facial recognition technology felt like an outlandish plot point of a 24 episode. These days, with almost ubiquitous surveillance in many urban areas and rapidly developing capabilities, it’s a key advantage of AI.

But serious questions remain about the accuracy of the information officials are using to arrest and convict people — and those concerns go far beyond cameras. LLMs trained on a limited diet of text, images, or characteristics could reproduce bias, for example, or spit out a result that’s not fully grounded in the factual evidence.

Wexler, who studies data, technology, and secrecy in the criminal justice system, says AI raises genuine concerns. But many of them are related to a broader lack of transparency about tech-aided evidence, she says, or even expert testimony from human beings.

“AI is, in a way, an opportunity, and it’s shining a spotlight on these issues that are relevant to AI but not necessarily unique to AI,” she says.

Wexler has written about how some software vendors use contract law protections to avoid peer review of their applications. That means police, prosecutors, judges, and juries are relying on results from devices and programs that haven’t been independently vetted to see if they’re returning accurate results.

AI is increasing that reliance, she says, and what Wexler calls its “shiny mystery” might sway jurors to defer the kind of skepticism they might have for a human expert. So when a police officer gets on the witness stand and describes the result they got from a device, they’re recounting the button they pushed — not the way the machine produced evidence.

Roth’s work, Wexler adds, points out that courts have ruled that there’s no Sixth Amendment right to cross-examine a software developer.

“These are sophisticated machines that extract data from a mobile device or a tablet. And they get up on the stand, and they say, ‘I used this system. I put the device in, I pushed a button, out came the data,’” Wexler says. If you ask, ‘How did that work?’ the answer is ‘I used it properly. I went to training and they told me to push this button, not that button.’

“But they don’t know anything about how the machine works inside.”

Identifying benefits

Other Berkeley Law scholars are exploring whether AI can be harnessed to improve the legal system. Chien, whose Law and Governance of Artificial Intelligence course will be the backbone of the LL.M. certificate program, has a forthcoming article that proposes using ChatGPT-style applications to improve access to the court system for low-income people.

For evictions, record expungement, and immigration, for example, a chatbot might help those who have difficulty finding or affording an attorney get the right legal advice or match up with a pro bono practitioner, she and her co-authors write. She also co-authored the first field study of legal aid attorneys using AI to improve service delivery.

“Generative AI technologies hold great potential for addressing systematic inequalities like the justice gap, but fulfilling this potential won’t happen organically,” she says. “More attention to the potential benefits, like reducing the cost of legal services for the underserved, and not just the harms, of AI, could have big payoffs.”

At the same time, that question of what inputs shape an AI-aided output continues to nag. In a 2022 essay, Katyal looks at cases involving AI decision-making to show how the concepts of due process and equal protection can be recovered, and perhaps even integrated into AI.

Berkeley Law’s Executive Education program offers AI training and programming (along with CLE credit) to legal practitioners and organizational leaders worldwide. Co-hosted with the Berkeley Center for Law & Technology, its annual Berkeley Law AI Institute is a three-day executive program exploring the intersection of artificial intelligence, law, and business. Generative AI for the Legal Profession is an online course designed for lawyers and others in the legal industry who want to harness the power of deep learning models, master key AI skills, and shape the future of legal practice.

“The debates over AI provide us with the opportunity to elucidate how to employ AI to build a better, fairer, more transparent, and more accountable society,” Katyal writes. “Rather than AI serving as an obstacle to those goals, a robust employment of the concept of judicial review can make them even more attainable.”

The safety risks are what grabs most people’s attention, Samuelson adds, particularly lawmakers. More than 700 bills seeking to rein in AI are floating around state legislatures, including a California bill sitting on Gov. Gavin Newsom’s desk that would force developers to create a “kill switch” for their software.

“The AI systems are powerful, and they’re often not explainable, and they make predictions, and they yield other kinds of outputs that will affect people’s lives,” she says. “There’s a lot of worry about discrimination, misinformation, and privacy violations.”

But as she pointed out to the European conference, the European Union’s generally proactive model of regulation may create a two-tiered system that stifles access to innovation and may work against the very goal it’s reaching for. It’s probably a misguided notion to think that big U.S. tech companies like Apple and Meta will agree to comply with new rules from Brussels, leaving smaller companies and European customers out in the cold.

Various forms of AI carry different risk profiles, she says, and applications for aviation, hospital record-keeping, and job recruiting shouldn’t get the same regulatory treatment. A nudge might be more effective than a hard standard, Samuelson argues.

“The people who are developing these systems are not trying to deploy them to destroy us all. They think they have some beneficial uses,” she says. “Then the question is, how do you balance the benefits of advanced technologies against the harms that they might do? And I think rather than mandating that everyone has to have a kill switch we could do something more targeted.”